Editorial by David Landriault

A Pelican Island “Land Bridge” Could Be Galveston’s Breakthrough Moment

An inspiring case for pairing economic growth with smarter flood protection.

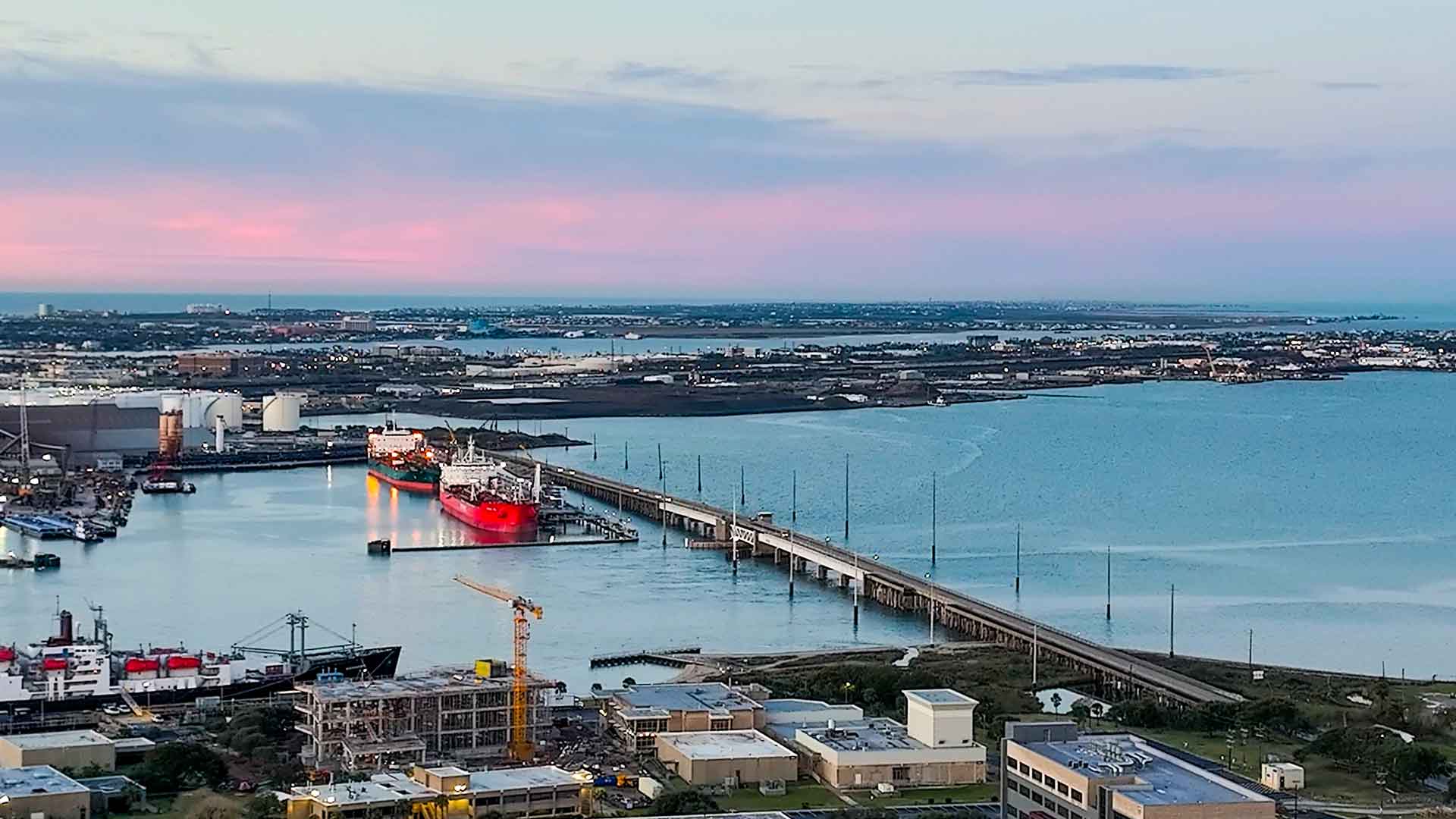

When a barge strike closed the Seawolf Parkway bridge, it exposed more than weak concrete—it revealed Galveston’s vulnerability. Now a bold idea is back on the table: a land bridge to Pelican Island that could double as flood protection and unlock a new era of industrial growth.

Key Facts at a Glance

- Barge strike & closure: May 15, 2024; waterway closed 6.5 miles for cleanup; bridge reopened with restrictions.

- Bridge estimate & timeline: Costs at $250M+ (peaking to $316M in some assessments); design underway; letting targeted for 2029.

- Local match & port support: City capped local share at $36.2M; Port of Houston approved $2M plus 13.78 acres for right‑of‑way.

- Land bridge back in play: Backed by port & maritime stakeholders; aims to add rail and new deep‑water frontage; previously paused over federal permitting concerns.

- Ike Dike context: Coastal Texas Program now ~$57B with inflation; Bolivar Roads gate the largest single feature; Galveston Ring Barrier key to benefits.

An 1839 Editorial: October 24, 2025

A Pelican Island “Land Bridge” Could Be Galveston’s Breakthrough Moment

On calm mornings, the Seawolf Parkway bridge looks almost serene—two narrow lanes, a tired lift span, and a steady trickle of students, shipyard workers, and families headed for Seawolf Park. But the illusion shattered on May 15, 2024, when a fuel barge struck the bridge’s supports, tearing concrete into the water, spilling oil, and severing the island’s only road. The route reopened with weight limits, but the message was unmistakable: Galveston is one barge strike away from isolation.

Since then, costs for the replacement bridge have surged—at least $250 million and climbing, according to state and local briefings—pushing the start of construction out to the 2028–2029 window and completion into the next decade. That timeline has revived a once-shelved idea: replace the span with a land bridge, a raised causeway that carries road—and possibly rail—between Galveston and Pelican Island. Supporters say it could do double duty: unlock industrial growth and form part of a modern ring levee for storm surge protection.

The moment that changed the conversation

The day after the 2024 strike, Galveston didn’t just have an infrastructure problem; it had a systems problem—single-point access to an island district that houses Texas A&M–Galveston, key maritime employers, and a growing shipbuilding cluster. Federal and state responders closed 6.5 miles of waterway to clean up the spill, a sobering preview of what a longer disruption could mean for the island’s economy.

A conventional fix is advancing: TxDOT’s new bridge would be a high fixed span with modern lanes and shoulders. But the price has ballooned (estimates from $250 million to $316 million surfaced in 2025), and the region still has to close a large funding gap. Meanwhile, letting is targeted for 2029, even if the money falls into place.

City Hall has done its part to keep momentum: Galveston capped its local match at $36.2 million in its Advance Funding Agreement, and this spring the Port of Houston approved an interlocal deal to contribute $2 million and convey 13.78 acres for right‑of‑way—signal boosts that the maritime sector needs this link rebuilt.

The bigger idea: a dual‑purpose land bridge

Here’s where the story turns from incremental to visionary. A fresh proposal circulating among port leaders and maritime companies (including Gulf Copper, Southwest Shipyard, Texas International Terminals, and the Ports of Houston and Galveston) argues that a causeway could reduce long‑term maintenance, enable long-sought rail access, and create new deep‑water docking frontage—transforming Pelican Island from a cul‑de‑sac into a competitive industrial platform. Think sea‑to‑rail logistics on day one.

Just as important: a raised causeway could be engineered to double as a levee segment—a protective spine that lets Galveston extend its ring barrier outward across Pelican Island, rather than forcing tall floodwalls through historic downtown along Harborside Drive. That concept could also pair with a closable floodgate on the port’s east side, encircling UTMB, Texas A&M–Galveston, downtown, and port assets within a single, storm‑ready envelope.

To be clear, regulatory agencies were wary the last time the causeway was floated (2018): closing a navigable channel triggers rigorous Coast Guard and Army Corps review, and that’s why leaders chose the bridge then. But the facts on the ground have changed—costs are up, risks are clearer, and industrial stakes are higher—and the idea is back in serious discussion. The land bridge has quickly gone from an idea whose time has passed to a forward looking vision with calls to study it as a flood defense alignment with economic upside.

Economics: a once‑in‑a‑generation industrial play

The “what‑ifs” around Pelican Island are gone. A White House–Finland pact now sets the course for up to 11 Arctic Security Cutters (ASCs)—four to be built in Finland and seven in U.S. yards—with an estimated $6.1 billion program cost and a first delivery targeted for 2028. U.S. production is slated for Davie in Galveston (three ships) and Bollinger in Houma, Louisiana (four ships), positioning Pelican Island as a frontline hub for polar shipbuilding.

To meet that demand, Davie Defense has unveiled a $1 billion “American Icebreaker Factory” plan to modernize the former Gulf Copper yard on Pelican Island—an investment expected to generate thousands of direct and supply‑chain jobs and anchor high‑skill maritime manufacturing here for decades. (Final contracting and regulatory approvals are in motion.)

What the pact changes for Galveston’s calculus:

- Rail + reliable access are no longer optional. Heavy components, long‑lead materials, and finished modules move cheapest and fastest by rail; a land bridge can be designed to carry road and rail while eliminating a single‑point failure at the old span.

- Build the spine once—then armor it. An engineered causeway can be armored as a levee‑grade structure, tying into a broader ring barrier and protecting the port, UTMB, Texas A&M–Galveston, and downtown from bay‑side surge—turning access infrastructure into coastal defense. (Surge hydraulics and tidal exchange would still require rigorous Corps/Coast Guard modeling and permits.)

- More waterfront, more throughput. Filling to form the causeway can create new berth frontage and staging areas along the alignment, expanding waterside capacity as icebreaker work ramps.

Advocates also note that a hardened causeway’s lifecycle costs (no lift machinery, far less painting/steel maintenance) could be a fraction of a long high bridge—claims TxDOT would need to validate in a formal alternatives review.

Meanwhile, the status‑quo bridge plan keeps sliding right under inflation. H‑GAC materials and local reporting now indicate construction beginning in 2029 with completion around 2034—a prudent but single‑purpose fix at a price already north of $250 million. If the region can “build once, solve two problems”—access and resilience—this is the moment to test it against the numbers.

And the money is moving: beyond the city’s capped $36.2 million local match, the Port of Houston has formally authorized a $2 million contribution plus 13.78 acres of Pelican Island right‑of‑way to advance the replacement—clear evidence that maritime stakeholders want a solution that supports industrial scale, not just minimum access.

Environment & surge protection: align protection where it helps most

The Coastal Texas Program (the “Ike Dike”) is now estimated at ~$57 billion with inflation—its largest component the Bolivar Roads surge gate across the bay’s mouth, paired with a Galveston Ring Barrier to block bay‑side surge. That ring is crucial: it’s where much of the project’s benefit is realized—protecting people, hospitals, the port, and the city’s tax base.

A Pelican Island levee‑grade land bridge could reshape that ring in a way that’s less intrusive and potentially more hydraulically efficient for downtown—pushing the defensive line outward, tying into high ground and existing dredge berms on the north side of Pelican, and enclosing critical port and university facilities. It’s the same surge logic—shorten the fetch, harden the perimeter—applied where the island’s economy now lives. (Any causeway would still need rigorous modeling to avoid harmful changes in tidal exchange and sediment transport—an explicit focus for the Corps in recent designs.)

What would have to go right

- Permits & Navigation: Prior Coast Guard/Corps concerns centered on navigation and hydrology. A feasible design could require culverts, sluiceways, or a small navigational opening—complexity that adds cost but preserves flow and safety. The trade is between lifecycle value and up‑front engineering.

- Program Integration: If Galveston advances a dual‑use causeway now, it should be explicitly interoperable with the Coastal Texas ring barrier, not in conflict with it—preserving eligibility for future federal dollars while delivering near‑term resilience locally.

- Financing: The current bridge already has H‑GAC funding programmed and a local match structure. A causeway alternative would need a comparable funding stack and a transparent cost‑benefit case showing access + rail + surge protection beats the single‑purpose bridge.

What’s next—and why this matters

This isn’t about nostalgia for a 2018 concept; it’s about aligning 2030s infrastructure with 2030s realities. Pelican Island is poised to be a national‑security shipbuilding hub, a maritime campus, and an industrial neighbor to downtown. A traditional bridge will restore access. A land bridge, engineered as levee and paired with a harbor gate, could future‑proof it. In a city that raised itself by 17 feet after 1900, that kind of ambition is familiar.

Galveston can choose the pragmatic path (the span already in design) or the transformative one (a dual‑use causeway that ties our economy to our safety). Either way, the clock is ticking—on cost inflation, on storm seasons, and on opportunities that won’t wait forever.

David Landriault

Founder of The 1839

David Landriault serves as the Founder of The 1839 and Co-Founder of Falcontail Marketing & Design. Under his leadership, Falcontail has grown into a boutique firm known for collaborating with a diverse range of distinguished clients. The firm’s portfolio includes notable names such as Stanford University, the Galveston Economic Development Partnership, Sunflower Bakery & Cafe, and other esteemed organizations.

Sources & References

- Associated Press. Barge hits bridge connecting Galveston and Pelican Island, causing oil spill. May 15, 2024.

- Associated Press. US Coast Guard says Texas barge collision may have spilled up to 2,000 gallons of oil. May 16, 2024.

- Houston Chronicle. Galveston’s Pelican Island bridge replacement needs funding gap; aging span damaged after barge strike. June 1, 2025.

- Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT). Seawolf Parkway at Pelican Island Channel Bridge — Project page.

- Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT). Seawolf Parkway at Pelican Island Channel Bridge — Public hearing & project info.

- Houston Chronicle. New bridge seen as ‘game changer’ for Galveston, Pelican Island land-use potential. April 29, 2016.

Join the Conversation

Galveston Pictures and Videos

Get Involved with The 1839

Sign Up for Our Newsletter